A brief history of Mother Ludlam’s Cave

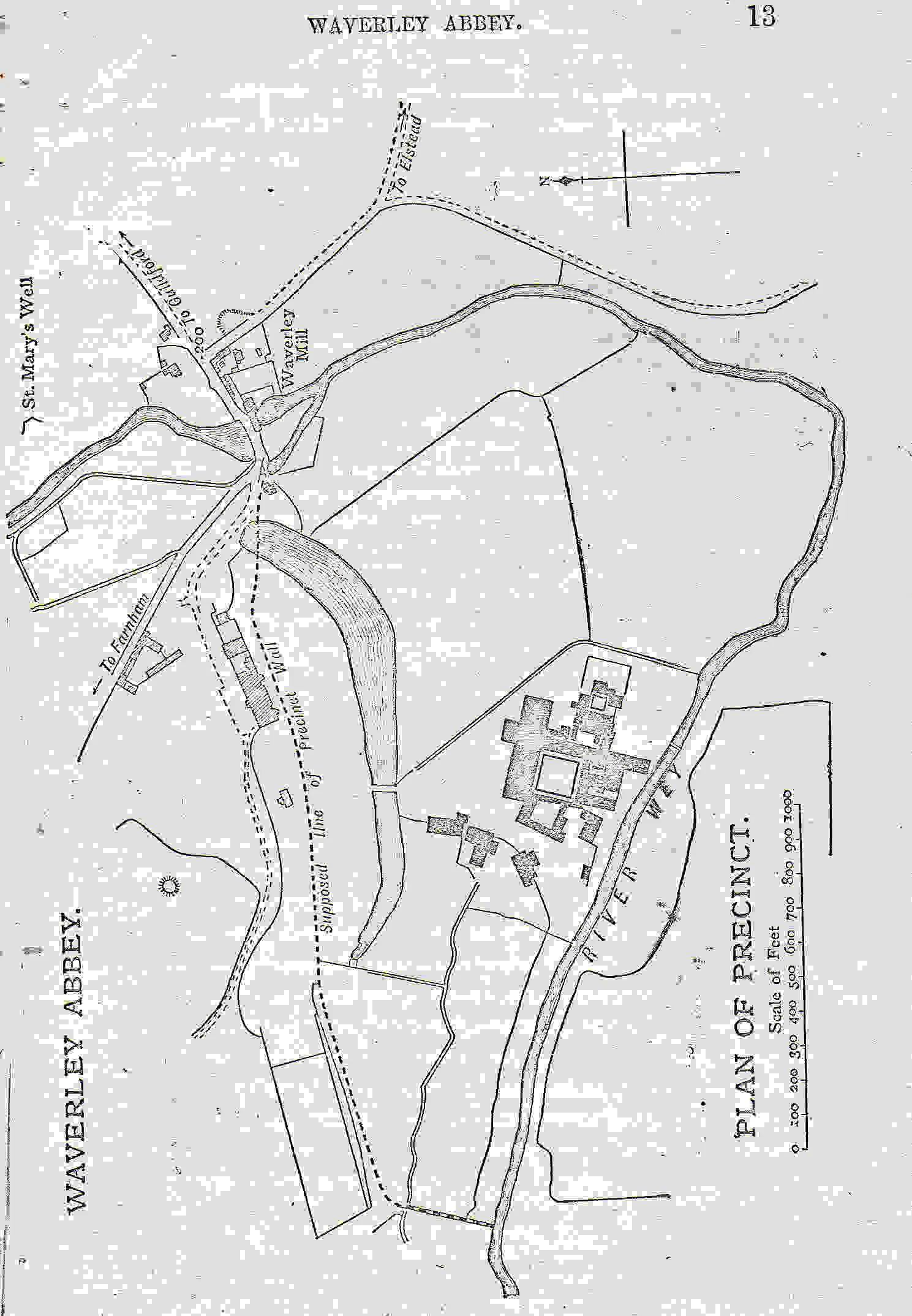

Mother Ludlam’s Cave sits in Moor Park beside the River Wey, a sandstone grotto shaped by springs and careful hands. Medieval water works in the valley supplied nearby religious houses, and later owners framed the opening as a place to pause, with paving, seats, a basin and a channel for the flow. By the nineteenth century the grounds were valued for fresh air and water, the entrance gained a protective arch and locked gates, and visitors recorded both improvement and decline as fashions changed.

The name Mother Ludlam belongs to local legend. She is remembered as a white witch who lent household things on trust, most notably a great kettle, and who withdrew her favour when a promise was broken. Versions speak of a chase across the hills and a treasured pot kept safe. The story clings to the sandstone and the river light, giving history a human voice.

Some mentions of the cave…

“It is really quite astonishing and utterly unaccountable what this week has done for me.”

— Charles Darwin in relation to his visit to Moor Park & the cave in 1857

“It is not the enchanting place that I knew … the basins … are gone … the pavement all broken to pieces..”

— William Cobbett on visiting the grotto (1825):

Myths & Legends

The cave is a small sandstone hollow in the Wey Valley at Moor Park near Farnham, with a spring historically recorded as Ludwell or Ludewell. Etymologies point either to a Celtic root meaning “bubbling spring” or to Old English “hlūd well,” while modern folklore links the name to the figure Lud.

Celtic layers and sacred spring claims

Many repeat a local claim that the spring site was sacred to the Atrebates, and ties Ludwell to Lud, a Celtic god-king associated with healing, London, and the Trinovantes. Treat this as a folkloric overlay rather than established archaeology, but it remains a persistent strand in retellings.

Mother Ludlam is remembered as a benevolent “white witch” who lent household items on trust, especially a great cauldron, with a strict two-day rule for returns. Earlier versions sometimes lean toward fairy agency rather than a witch, which is why the legend reads differently across periods.

The broken promise and the cauldron:

A borrower failed to return the cauldron on time, ending the lending custom. The vessel is now associated with Frensham Church, where a large medieval copper cauldron survives. Historians note such cauldrons had practical parish uses, which explains its presence even if legend gave it a story.

Devil’s Jumps variant:

In one popular version, the Devil stole the cauldron, fled in great bounds that formed the sandstone hills called the Devil’s Jumps near Churt, dropped the “kettle” on Kettlebury Hill, and Mother Ludlam recovered it for safekeeping at Frensham.

Fairy variant on the ridge:

A twentieth-century telling places fairies on the highest Jump, with the borrower whispering through a rock hole to obtain the cauldron. When the rule was broken the cauldron hounded the borrower until he reached church sanctuary, where he died and the vessel remained.

Clippings…

Below you’ll find various mentions of the cave in a number of books, research pieces and newspapers